Masahista - The Masseur Directed by Brillante Mendoza

Masahista - The Masseur

Directed by Brillante Mendoza

Starrings: Coco Martin, Jaclyn Jose, Alan Paule, Katherine Luna, R.U. Miranda, Aaron Rivera, Arianne Camille Rivera, Ronaldo Bertubin, Norman Pineda, John Baltazar, Jan-el Esturco, Erlinda Cruz, Rose Mendoza, Mary Anne de la Cruz, Maximiano Sultan, Randell Reyes, Paolo Rivero, Kristoffer King, Marvin Bautista, Kim Redoble, J.D. Basco, Joe Armas, Jetro Rafael

Country: Philippines

Year: 2005

Author Review: Roberto Matteucci

Click Here for Italian Version

“Sir, the kiss on the lips is meant for the girlfriend.”

Galvanized by exponential increases in GDP, in Southeast Asia, a modern, educated, universal and traditional cinema is being produced. The filmmakers studied, learned international lessons but kept the communication channel open with their country. Making choices, creating their own style, exploiting far-reaching stories, adapting and conveying messages make them even more influential than the decadent West.

They have an infatuation for cinema. They understand the flavours of their culture and they have intelligence and a lot of patience.

Among many examples are Thai Apichatpong Weerasethakul and Filipino Brillante Mendoza.

Tropical Malady, Apichatpong Weerasethakul

Apichatpong Weerasethakul is poetic. He penetrates the heart of Thailand's soul and into its settings: the forest, the voices of the souls, the ghosts. In the mysterious Tropical Malady - Sud pralad, two young lovers spend time together. In the second part, one of the protagonists gets lost in the jungle. The lush rainforest is the territory of human loneliness, but it is full of sounds and sights of life too. The same also occurs in Uncle Boonme who remembers his previous lives - Loong Boonmee raleuk chat. Uncle Boonme dissolves himself into nature, into the forest: "you manage the company and then after I die I'll come back to help you."

Brillante Mendoza, from Philippines, uses an outwardly social approach. He is deeply involved in the Filipino family with its contradictions and contrasts.

These are the characteristics of Mendoza's film presented at the Venice Film Festival in 2012: Thy Womb – Sinapupunan. The same ideas in his first film, Masahista – The Masseur, winner of the 2005 Locarno Film Festival.

Thy Womb - Sinapupunan, Brillante Mendoza

Thy Womb - Sinapupunan is the story of a couple. The wife cannot have children. A common problem, however, translated by Mendoza into a spectacular atmosphere. The protagonists are Bajau, a Muslim population that dwells on the water on wooden stilts in the southern Philippines. He narrates Shaleha's drama. She is a village midwife, incapable of giving her husband a child. It was directed with intense, slow sequences and minimal dialogue.

In Masahista, Brillante Mendoza has an identical style. He shocks the audience by telling with sweetness and realism. The protagonist is Iliac, a masseur for men in a brothel on the Manila outskirts. The director's style repeats. Social adaptation, the difficulties of complicated growth are the Iliac's scenario, his sufferings and his family.

Brillante Mendoza's cinema is characterized by an enlightening and sophisticated social intimacy. The styles are shaken with balance. It is his special gift. His artistic talent prevails with alternating editing, dissolving, matches, particulars, interweaves that are never fast, yet precise and deliberate.

Iliac is a handsome guy. He has a vigorous physique, we do not know his past or his reasons for working as a masseur. Did he choose to prostitute himself in a brothel for his powerful muscles? Or because he has no additional skills to emerge? He has a family: a little brother, a sister, a mother and a father.

Brothel and family are his ambivalent environments. Space and time intersect; despite the plot being linear. Iliac is misaligned for one day. Twenty-four hours before he worked and the day after he buried his father. There is a peculiar plot. The author uses this stylistic feature to affirm the overlap between eroticism and death.

At the beginning, there is an Iliac's subjective shot in a car, in a taxi and then in a rickshaw. He is going to San Fernando, where he lives, after a night in labour. He crosses fields, buildings, huts and arrives at his destination, a hospital. He has certainty about his father's death. His family is in the mortuary.

The director inserted the scenes from the evening before the job skilfully and seamlessly.

Alfredo selected Iliac by chance. Alfredo's favourite prostitute had hurt his foot. The journey home is quick, by car and scooter. Brillante Mendoza mixes detailed frames with some mannerisms: a long and calculated clash between a rickshaw and a horse-drawn carriage. The walk to the clinic is filmed with the use of slow motion to disturb the boy's emotions. All are underlined by primary colours such as green and yellow.

The family does not appear sad about the man's death. They are freed from a burden, although her mother respects popular conventions and she organizes a dignified ceremony.

The frames are long shots to emphasize Iliac in his conduct and his search for family principles. Humanity locked up in a massage centre is different. It is a place of perdition. Life proceeds erotically and discreetly. Inside, there is an affable relationship, a request for affection and sex. When time runs out, as in the Cinderella fable, everything turns out to be an unreal illusion.

Let's forget the phosphorescent Gogo bars of Bangkok. The Philippine brothel is an isolated, autonomous, reserved compound; whoever enters knows what he finds. It has its own laws, it is a totalitarian world of sexy guys.

“Sir, all the masseurs here are stallions” the customers are ambiguous characters. For Philippine society, homosexuality is a weakness and not a free option to enjoy voluptuously.

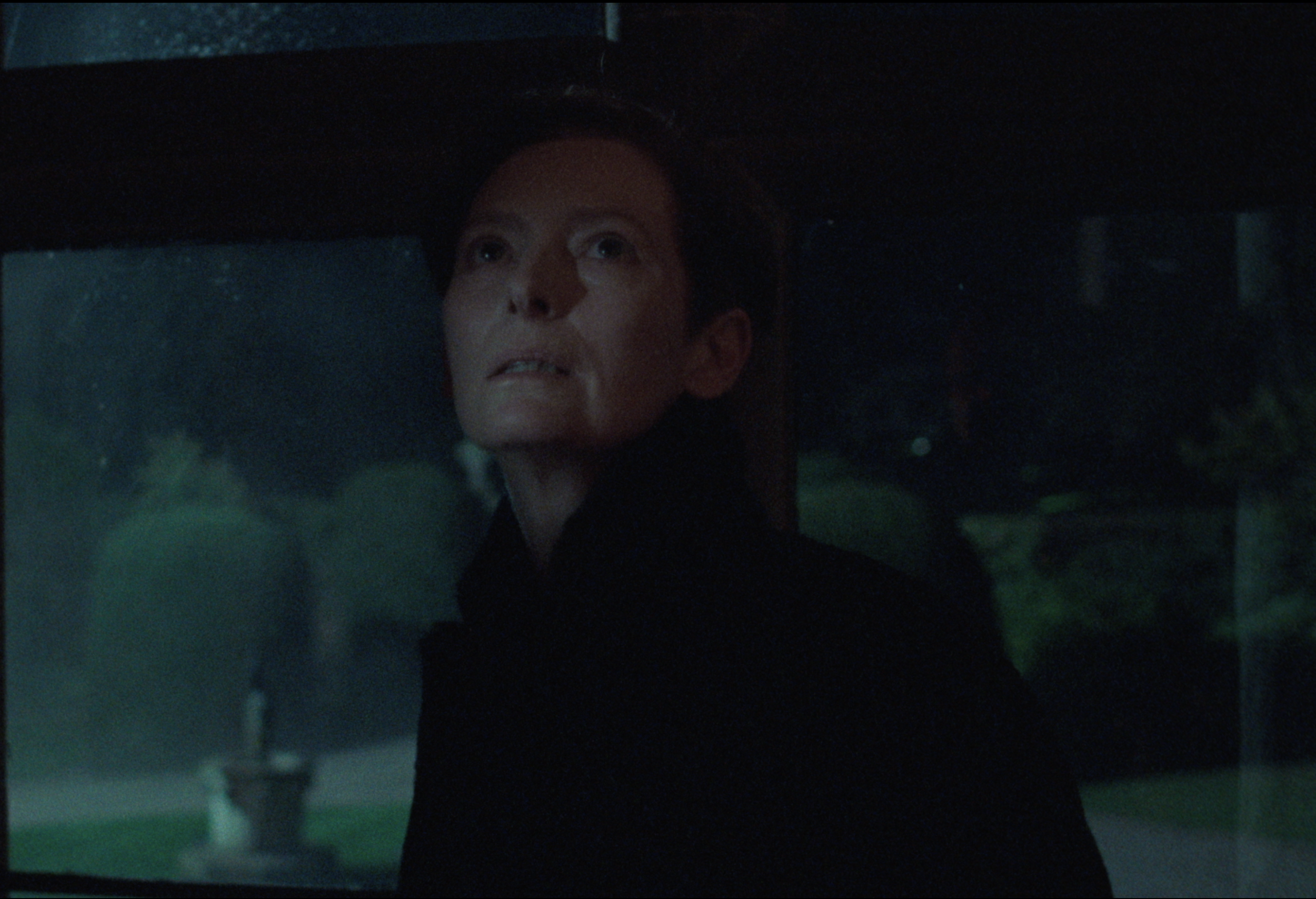

The brothel is the most familiar location for Iliac. The family is dazed, full of unclear tensions. Therefore, Iliac is simple, not flashy but intimately libidinous and erotic. The author describes the sensuality of using numerous young men. They are dazzling but confident teenagers, surrounded by bold tones such as dark red and green.

The brothel will not be able to prevent Iliac from his human turmoil. He ignores his mother's mobile texts, with the news that his father is hospitalized. He keeps them hidden but he has to cohabit with them while he continues to massage. The film shares space and time points.

Mendoza interlocks the periods, with some similar fades apparently happening around the same time.

In the brothel, Iliac is undressing Alfredo. Meanwhile, Iliac is also in the morgue, helping the undertaker dress his naked father.

While he is provocatively rubbing the man's foot, his dead father's feet sprout. Alfredo and Iliac's father are merging, due to identifying Iliac's emotional restlessness. His father has been absent, and Iliac compensates for his lack by taking care of a man, not exclusively for money. He speaks frankly to him cheerfully, confidently. There is a bond between them in the small room. Iliac would like to raise the relational level, although he has met him for about ten minutes; he encourages him to have a superior relationship, longing to see him again, to go out for Christmas shopping.

The editing is constructive. For instance, a detail of the brothel recalls the morgue. The places are nevertheless close.

Home, the mother has prepared a funeral wake, reciting Our Father. However, there is no distress. Everyone is distracted: they eat, play cards, gossip, laugh and above all, no one cries.

At the same time, the brothel is filmed from above. It is sold out, all the bedrooms are occupied. The director enchants with an aerial shot with a tracking camera through the rooms. In the cubicles, the masseurs are lewdly rubbing customers. The rooms are tiny, with various colours. The masseurs are filmed from behind and the guests are lying down. It is an assembly line, repetitive activity as if it were Modern Times of sex, but devoid of any ironic approach.

The bodies of horny adolescents represent a society to be elevated and changed. It is not controversial. It is not political disobedience, it is just physical exposure. He does not even scandalize. He plays indecently with bodies; nudity is short-lived but does not preclude strong carnality. The customers have an identical vision, and when invited by the effeminate manager, they are excited to observe the lucid sturdiness of the hustlers.

Libido is enhanced by perfect photography. In the rooms, there is only one source of light, highlighting their lubricity in chiaroscuro. Lust does not stop the masseur and client from talking.

“I have a cuckoo for a father” Iliac told Alfredo. Simultaneously, the father is dying of liver cirrhosis. Ilic knows it but is neither grieved nor indifferent. On the other hand, Alfredo hesitates enigmatically. He talks about his life. He is excited by physical contact. The warmth of Iliac's hands pushes on the nerves in his body. He might be married, but it is possible to listen to his mother's phone call. It is clearly a symbol. He lies shamelessly about where he is. He, too, has family troubles. They are starting to look alike. They are getting closer but it is an unworkable encounter.

They are two lonely people. Isolation is accentuated for Iliac by his vulgar, drunk, rowdy girlfriend, who is waiting for him outside. She screams, wheezes, argues, while in the cubicle, Iliac and the man exhibit their nakedness; they are from behind, with single lighting in this case too. A powerful exterior. The two solitudes are united for that brief moment, a green wall is separating them. Now, after a concise and ephemeral paid sex, they are near. If they had the courage and conscience to obtain civil emancipation, they could fight for a different and perhaps better existence, but they do not want it.

At the funeral service, everything is white. The sun deforms the figures amidst the disinterest of those present. A group of boys play basketball in the cemetery courtyard. The mother restores the right morals. She begins crying disconsolately, unhappy. Why? For an unloved husband? No, she wants to bring back the exact dimension of family love, whether good or bad.

It is like Shaleha, the midwife of Sinapupunan. She will accept her destiny without indecision. Her purpose was to give her husband a child. It does not matter if he kicks her out after her birth. The same false fate will happen to Iliac.

The massage becomes more passionate. Alfredo turns into a father, both accumulate. He remains at work. He is aware of his parent's death. Rapid editing leads to both moments.

Alfredo asked him for the final coitus. They are returning to reality, abandoning the fallacious and deceptive activities of the multicoloured brothel.

The man fucks him angrily. His mind is tied to an unattainable independence. He will never be able to accept it, condemned to perpetual behaviour.

Iliac is unhappy and hurt by violent copulation. That is not all. His life is crumbling. His face is melancholy, divided in two sections. The first one is bright and the other is dark. He does not smile anymore. The friendly attitude, shown to the man, vanishes in those few irritable happy end.

Iliac's final cry, discouraged by his situation, connects him with Shaleha's departure. They are divided and will have to reorganize their lives.

Brillante Mendoza outlines Iliac with dedication, accompanying him with veneration.

Revenge and forgiveness belong to three Mexican boys intent on organizing their retaliation in the film A cielo abierto - Upon Open Sky by directors Mariana Arriaga and Santiago Arriaga presented at the 80th Venice International Film Festival.